The Patient Capital Review – what does the data say?

Category: Uncategorized

Beauhurst supplied data for the Government’s consultation Financing Growth in Innovative Firms, and has now submitted its response to the government’s Patient Capital Review – a summary of which is below.

The problem: are companies struggling to scale?

605 companies raised seed rounds in 2011, 39 of which are now growth-stage. Based on the funding those companies used to scale, we estimate that an extra £8.9bn of investment (over six years) would have been required to enable the remaining businesses to reach growth-stage. Given that more than 7,000 companies have raised seed rounds since then, the overall requirement is more like £100bn.

This assumes, of course, that all firms which raise a seed round are capable of reaching growth-stage, and that those that did not were only lacking capital. It also assumes that all companies require a similar amount of capital to scale, which of course is not necessarily true (a pharmaceutical firm might require much more intensive funding than, say, a food delivery startup).

Nonetheless, the figures are stark, and 19% of the 2011 companies remain at the seed-stage six years on. That’s a strong indicator that patient capital is required.

What does patient capital look like right now?

The Treasury’s initial consultation, Financing Growth in Innovative Firms, identified crowdfunding as a positive contribution to the patient capital landscape. We’re not convinced, however, that there’s enough data to draw such a firm conclusion yet.

Instead, it’s likely that crowdfunding will be a mixture of patient and non-patient, given the diversity of investments it facilitates. In short, sometimes crowdfunding campaigns will be helpfully patient, and sometimes they will be damagingly impatient.

We’re also concerned that activity by the British Business Bank and the European Investment Fund might not be the answer to the patient capital shortfall. Both invest into UK-based venture capital firms – most of which operate with investment horizons of 8-10 years. That timeline isn’t what’s traditionally considered patient: we actually found that the average age of acquisition for a high-growth UK company is 13.5 years, and the average IPO happens when a company is 10 years old.

Why isn't there more of it?

Because investors aren’t convinced that it yields better returns. Traditional PE and VC firms already make good returns; truly patient capital’s record is unproven. So investors are waiting on strong evidence that patient capital works, or – failing that – some kind of guarantee that they wouldn’t lose money by investing in such a risky way.

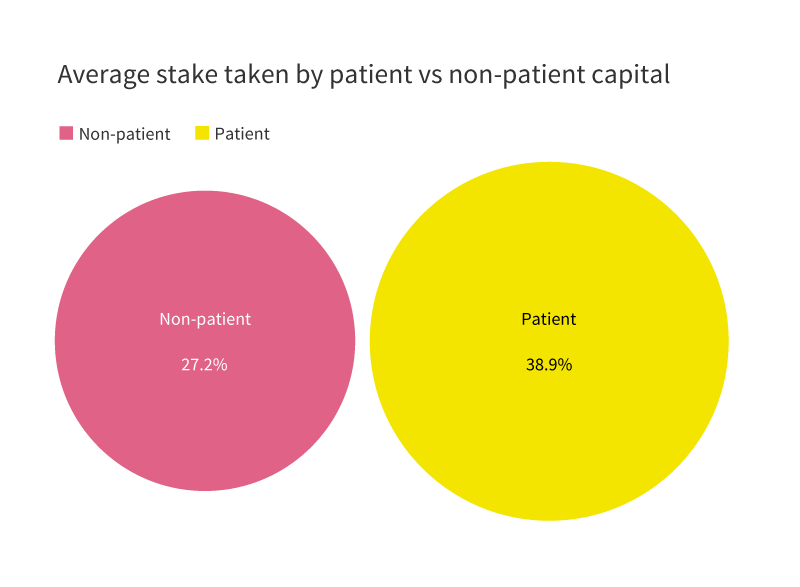

Entrepreneurs might not be that enthusiastic to take patient capital, either: patient investors typically take a larger stake, as we showed previously. If those offering long-term investment demand more in return, it’s possible that they themselves are putting young companies off patient capital.

Of course, it’s also likely that many founders simply don’t know what patient capital can bring to their business. We suggest taking a look at those like BGF, who take a leading role in educating founders about equity investment and its benefits.

What's stopping big investors from supplying patient capital?

By ‘big investors’ we mean pension funds, insurers, banks, family offices, corporates, and overseas investors – amongst others. There are two problems here (which were conflated in the initial consultation): how to encourage these institutions to make equity investments into private UK companies, and how to encourage them to make those investments patient.

At the moment, many of these bodies invest as limited partners into VC funds (rather than making the investments directly). This is good and important, but the VCs aren’t always patient. The government could either encourage this fund structure to change in favour of patience, or encourage the bodies to become LPs in other, more patient vehicles like listed investment companies (a process which might benefit from tax benefits, like those attached to investing in VCTs, alongside rules about what kind of makeup the vehicles’ portfolios ought to have) – or in non-listed open-ended investment companies (OEICs).

The solution: what can be done?

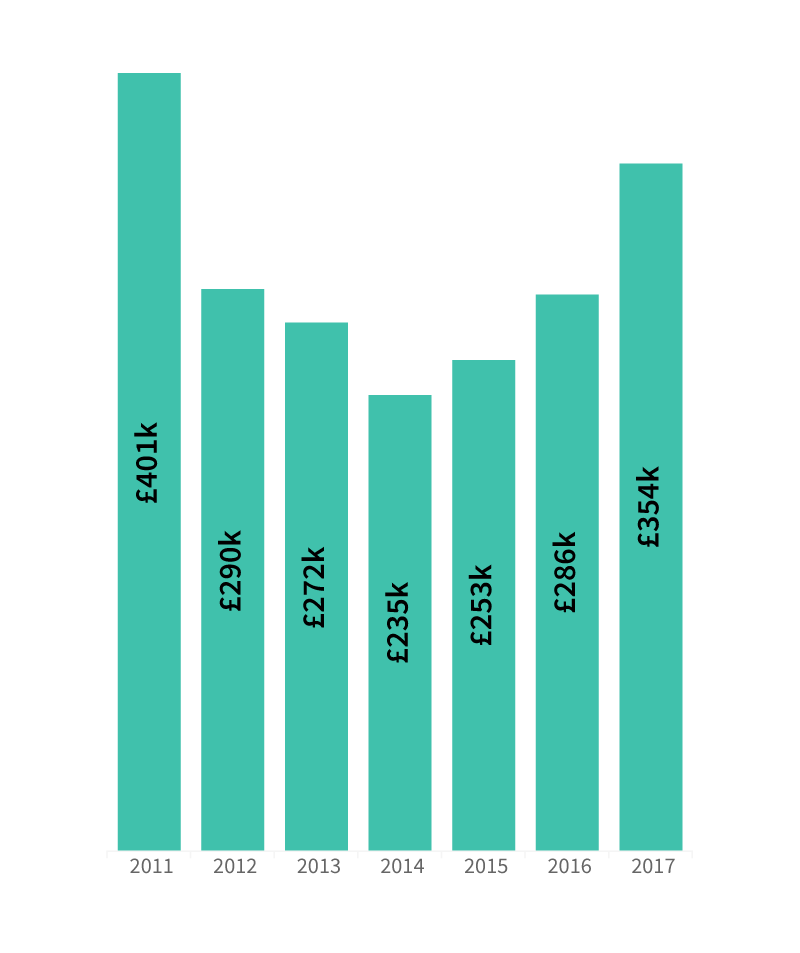

SEIS and EIS (explained here) are both very important – as are the business angels who make use of them. But the SEIS limit, introduced in 2012, appears to have encouraged companies to raise smaller initial rounds in order to attract those investors (see graph). Increasing the limit might prevent this downwards pressure.

The schemes also require investors to hold shares for a minimum of three years in order to reap the benefits. But three years is hardly the timeline of patient capital. Why not introduce further reliefs for those who hold onto shares for longer? This would de-risk and thus incentivise patient investing, and the more closely the reliefs were linked to the length of time shares were held, the better the incentive structure that would result.

Finally, government could invest – as opposed to simply offering reliefs – through listed OEICs, in order to attract institutions like those we discussed above to do the same by creating increased liquidity. We recommend that government focus on creating more OEICs, both listed and unlisted, across the board.

In light of losing investment from the European Investment Fund, we also make the bold suggestion of creating a listed investment vehicle supported by either the government itself or the British Business Bank, which would have exposure to all stages of innovative companies as follows:

Seed-stage companies

Innovate UK has considered the possibility of offering equity investment, and is currently piloting debt investment. This new fund could invest from its balance sheet to acquire IUK’s stakes.

Venture-stage companies

Enterprise capital funds have done excellent work stimulating seed-stage and growth-stage investments, but are not fully patient. If this single fund were to buy out their holdings, ECFs’ investment timeline could be lengthened.

Growth-stage companies

The fund could either buy equities from listed OEICs to increase liquidity in them by creating more pricing events, or buy OEIC shares to create liquidity directly. If the fund were itself listed, government would be able to sell stakes in it as its track record was proven.

Henry Whorwood leads Beauhurst’s consultancy team.

He has recently undertaken bespoke work for the British Business Bank, SyndicateRoom, Innovate UK, and Ernst & Young.